Pelvic Organ Prolapse

What is pelvic organ prolapse?

It is a very common condition, particularly among older women. It's estimated that half of women who have children will experience some form of prolapse in later life, but because many women don't seek help from their doctor the actual number of women affected by prolapse is unknown. Read on to learn about the different types of prolapse that can occur, and find information about causes, diagnosis, treatment options and prevention as well as what you can do to help ease your symptoms.

Prolapse may also be called uterine prolapse, genital prolapse, uterovaginal prolapse, pelvic relaxation, pelvic floor dysfunction, urogenital prolapse or vaginal wall prolapse.

Types of Prolapse

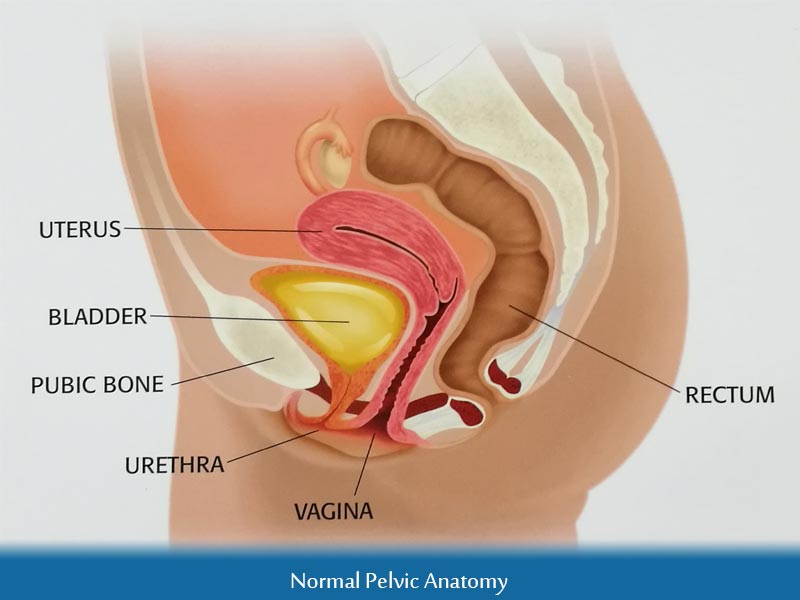

Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when the pelvic floor muscles become weak or damaged and can no longer support the pelvic organs. The womb (uterus) is the only organ that actually falls into the vagina. When the bladder and bowel slip out of place, they push up against the walls of the vagina. While prolapse is not considered a life threatening condition it may cause a great deal of discomfort and distress.

There are a number of different types of prolapse that can occur in a woman's pelvic area and these are divided into three categories according to the part of the vagina they affect: front wall, back wall or top of the vagina. It is not uncommon to have more than one type of prolapse.

Prolapse of the anterior (front) vaginal wall

Cystocele (bladder prolapse)

When the bladder prolapses, it falls towards the vagina and creates a large bulge in the front vaginal wall. It's common for both the bladder and the urethra (see below) to prolapse together. This is called a cystourethrocele and is the most common type of prolapse in women. Urethrocele (prolapse of the urethra)When the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder) slips out of place, it also pushes against the front of the vaginal wall, but lower down, near the opening of the vagina. This usually happens together with a cystocele.

Prolapse of the posterior (back) vaginal wall

Enterocele (prolapse of the small bowel)

Part of the small intestine that lies just behind the uterus (in a space called the pouch of Douglas) may slip down between the rectum and the back wall of the vagina. This often occurs at the same time as a rectocele or uterine prolapse (see below).

Rectocele (prolapse of the rectum or large bowel)

This occurs when the end of the large bowel (rectum) loses support and bulges into the back wall of the vagina. It is different from a rectal prolapse (when the rectum falls out of the anus). Uterine and vaginal vault prolapse (apical or top)

Uterine Prolapse

Uterine prolapse is when the womb drops down into the vagina. It is the second most common type of prolapse and is classified into three grades depending on how far the womb has fallen.

Grade 1

The uterus has dropped slightly. At this stage many women may not be aware they have a prolapse. It may not cause any symptoms and is usually diagnosed as a result of an examination for a separate health issue.

Grade 2

The uterus has dropped further into the vagina and the cervix (neck or tip of the womb) can be seen outside the vaginal opening.

Grade 3

Most of the uterus has fallen through the vaginal opening. This is the most severe form of uterine prolapse and is also called procidentia. Vaginal vault prolapseThe vaginal vault is the top of the vagina. It can only fall in on itself after a woman's womb has been removed (hysterectomy). Vault prolapse occurs in about 15% of women who have had a hysterectomy for uterine prolapse, and in about 1% of women who have had a hysterectomy for other reasons. Describing the severity of a prolapseMost women, and their doctors, describe the severity of a prolapse simply as mild, moderate or severe.

There is, however, a grading system that uses numbers to describe the extent of a prolapse. In the past, the grading system for uterine prolapse (1, 2, 3) was also used for other types of prolapse. This wasn't technically accurate, and a new, more precise classification system has recently been developed.The new grading system uses a series of measurements and is fairly complicated, but generally categorizes the severity of prolapse into stages I, II, III or IV. Stage I is mild prolapse. Stage IV is severe prolapse. Some doctors may still refer to prolapse using the older classification of 1, 2 and 3.

Pelvic organ prolapse

Causes of uterine and bladder prolapse

Risk Factors

Normally, the pelvic organs are held in place by the pelvic floor muscles and supporting ligaments, but when the pelvic floor becomes stretched or weakened, they may become too slack to hold the organs in place. A number of different factors contribute to the weakening of pelvic muscles over time, but the two most significant factors are thought to be pregnancy and ageing.Pregnancy & childbirth Pregnancy is believed to be the main cause of pelvic organ prolapse - whether the prolapse occurs immediately after pregnancy or 30 years later.

The weight of the baby, and the physical trauma of labour and birth, stresses and strains the pelvic muscles and ligaments. Some of the tissues that become damaged during pregnancy never fully regain their strength and elasticity.

Certain situations in pregnancy and birth further increase the likelihood and extent of damage, such as a large baby, a long labour and the use of forceps or extraction devices. There is conflicting information about the effect an episiotomy (a cut made in the base of the vagina during childbirth) may have on a woman's risk of prolapse, but the most recent research suggests it does not prevent pelvic floor damage.

Women who have more than one child, whether the delivery is vaginal or by caesarean section, have a higher risk of prolapse than women who have one child or no children at all. Some people believe a caesarean section may be less damaging than a vaginal birth, but the majority of studies suggest that it is only slightly, if at all, protective. Studies also suggest that women who have children in close succession are at an even greater risk of prolapse because the muscles and ligaments are under constant strain.

Aging and the Menopause

Our muscles weaken as we grow older and the pelvic muscles are no exception. Although tissue damage is likely to have been caused much earlier, the ageing process further weakens the pelvic muscles, and the natural reduction in oestrogen at the menopause also causes muscles to become less elastic.

Obesity, large fibroids or tumors

Women who are severely overweight, or have large fibroids or pelvic tumours, are at an increased risk of prolapse due to the extra pressure this creates in their abdominal area.

Chronic Coughing or Strain

Chronic (long-term) coughing, from smoking, asthma or bronchitis for example, or the straining associated with constipation, increases a woman's risk of prolapse. A few bouts of bronchitis or constipation are unlikely to have a serious effect on your pelvic muscles, but if the stress and strain is ongoing, it may eventually weaken the pelvic support structures.

Heavy Lifting

Heavy lifting can also strain and damage pelvic muscles and women in careers that involve regular manual labour or lifting, such as nursing, have an increased risk of prolapse.

Genetic Conditions

Women with a genetic collagen deficiency (Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) have an increased risk of prolapse even if they don't have any of the other risk factors. Collagen is a natural protein that helps keep tissues plump and elastic. Without it, the pelvic floor muscles become weak.

Previous Pelvic Surgery

Pelvic surgery, including hysterectomy or bladder repair procedures, may damage nerves and tissues in the pelvic area increasing a woman's risk of prolapse.

Spinal Cord Conditions and Injury

Spinal cord injury and conditions such as muscular dystrophy and multiple sclerosis dramatically increase a woman's risk of prolapse. If the pelvic muscles are paralysed or movement is restricted, the muscles waste away and cannot support the pelvic organs.

Ethnicity

Studies show that white and Hispanic women have the highest rate of pelvic organ prolapse, followed by Asian and black women. There is little information about the incidence of prolapse in women of other (or more specific) ethnic groups.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Symptoms And Diagnosis Symptoms:

Women with mild prolapse may have no symptoms or discomfort at all and may not be aware they have a prolapse. When symptoms do occur, however, they tend to be related to the organ that has prolapsed.

A bladder or urethra prolapse may cause incontinence (leaking urine), frequent or urgent need to urinate or difficulty urinating.

A prolapse of the small or large bowel (rectum) may cause constipation or difficulty defecating. Some women may need to insert a finger in their vagina and push the bowel back into place in order to empty their bowels.

Women with uterine prolapse may feel a dragging or heaviness in their pelvic area, often described as feeling "like my insides are falling out".

With severe prolapse, when the uterus is bulging out of the vagina, the skin may become irritated, raw and infected. Symptoms that may be occur with all types of prolapse:

- Feeling a lump or heavy sensation in the vagina

- Lower back pain that eases when you lie down

- Pelvic pain or pressure

- Pain or lack of sensation during sex

Diagnosis

If you have any of the symptoms of prolapse, particularly if you can see or feel something near or at the opening of your vagina, make an appointment to see your medical doctor.

Many women with prolapse avoid going to the doctor because they are embarrassed or afraid of what the doctor might find, but prolapse is very common and is nothing to be ashamed of.

Before you see your doctor, it may help to make a list of symptoms, concerns and questions. Take the list with you to your appointment. It may be difficult at first to talk about your symptoms, and some women find the examination uncomfortable, but it only takes a few minutes. And by having your symptoms checked you are taking an active role in your health and well-being.

What to expect at your appointment

To look for signs of prolapse your doctor will need to do a thorough pelvic examination.

You will be asked to undress from the waist down and lie on your back on the examination table. You should be given a blanket or sheet to put over yourself but if you aren't, just ask for one. The doctor will ask you to bend your knees and let them fall open. Some women find this position difficult, so if you can't lie this way, say so. The doctor can do the examination with you lying on your side with your knees drawn up in the foetal position. In fact, many doctors will do this anyway when looking for prolapse as it's a good way to check the front and back walls of the vagina. The doctor will feel for any unusual lumps or bumps in your pelvic area by inserting two fingers in your vagina and pushing gently on your abdomen. You will be asked if you feel any pain or discomfort. Tell the doctor if it hurts even if you are not asked.

The doctor may also insert a special speculum (called a Sims speculum) to examine the walls of the vagina for bulges. You may be asked to cough or strain during the examination. This enables the doctor to see if any urine leaks or if any of the pelvic organs prolapse into the vaginal walls. Some prolapse symptoms go away when you're lying down, so your doctor may also want to examine you while you're standing. If you have bowel symptoms the doctor may need to feel for bowel prolapse by placing one finger in your rectum and another in your vagina and asking you to strain or bear down. If you have urinary symptoms, the doctor should take a urine sample to check for a urinary infection.

Questions to ask your doctor about your prolapse

- What type of prolapse do I have?

- How severe is it?

- Do I need treatment and if so, what treatment do you recommend and why?

- What if I choose not to have any treatment?

- What can I do to ease the symptoms?

An intimate examination can be unnerving and many women (and men for that matter) find it difficult to remember everything that is said during the appointment, particularly if the doctor uses technical terms. It may help to write down the answers to your questions.

A good doctor will explain what s/he is doing throughout the examination but if you have any questions, ask for an explanation. If you have a mild prolapse that isn't causing you any pain or discomfort, you don't need treatment. There are, however, some steps you can take to help improve your prolapse and prevent it from getting any worse, see Preventing Prolapse

If you develop any new symptoms or your existing symptoms get worse, contact your doctor. Because symptoms often develop gradually it may be difficult to judge when you should go back to the doctor. There's no right or wrong answer, but as a general guideline, tell your doctor if:

- Pain or discomfort is interfering with your daily activities

- Sex becomes painful

- You can feel or see something bulging out of your vagina or just inside your vagina

- You have any unusual bleeding or discharge

- You develop any of the other symptoms mentioned above

If your prolapse is moderate or severe and is causing pain or discomfort, you should be referred to a urogynecologist for further investigations and possible treatment.

The specialist will ask you about your symptoms and health history and will examine you again to make sure the diagnosis is as precise as possible. If you have bladder symptoms the specialist may do additional urine and bladder tests to check if the symptoms are related to your prolapse or separate from it. Incontinence will need to be treated in addition to treating your prolapse.